Hey folks, this is going to be a long post. Maybe one of the longest posts we’ve ever written here and that’s because we intend it to be a useful tool for people to get introduced to Artificial Intelligence (AI) technologies if you’ve just been reading headlines about AI for the last 2-3 years.

Second, yes, both the title image and the header image are AI generated pictures. We pulled them from our stock image provider, Lightstock. We do not intend to use AI generated pictures often, but this time felt appropriate.

As a self-professed tech pessimist, the piece of technology I’m most pessimistic about right now is Artificial Intelligence (AI). I believe there are very serious issues with AI technologies; the way they are being adopted, the things machines are generating, and the people they are displacing (like how one report found that women are far more likely to lose their job to AI, versus men).

But before I get to the pessimistic part, let me outline some ways I’ve really enjoyed using AI, and ways that I believe it is currently being used to great benefit for many people, including the church.

The Good

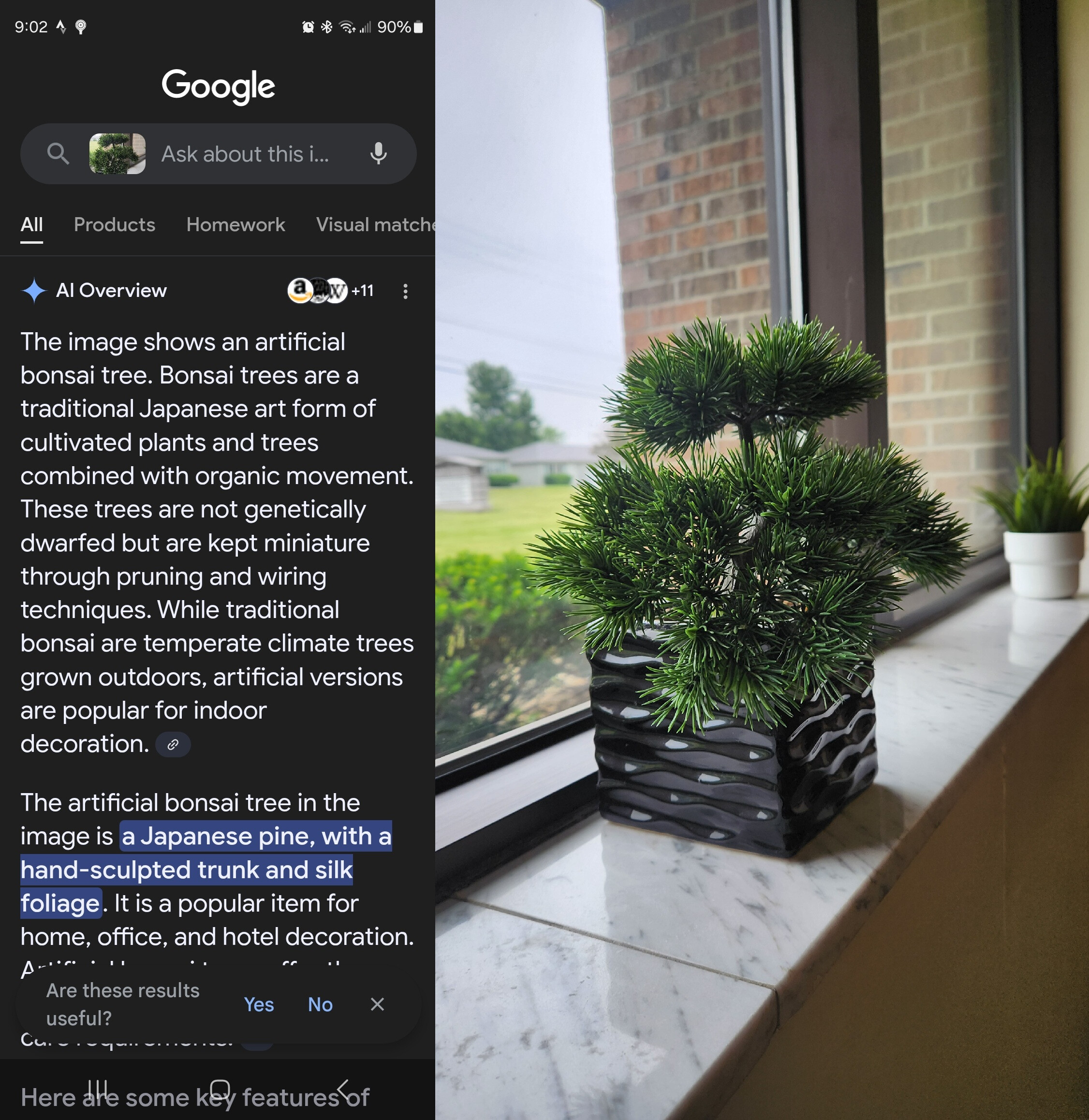

In a surprise even for myself, I’ve had a lot of fun using machine learning algorithms (what we often call “AI”) to help me identify plants using Google Search. I can tap the “Google Search” app on my phone, hit the camera icon in the top right, and snap a picture of whatever tree or plant I don’t know the name of. Withing seconds, all information I could ever want about a plant, including its name, the right planting season, how much water and sun it needs, pictures, and more are made available to me.

It even accurately clocked the artificial bonsai tree that my wife put in my office.

It’s an amazing piece of technology that cuts through communication and knowledge barriers. Before, if I had wanted to start learning about plants to identify them, I’d have to go buy a book, or start browsing lots of plant-based websites, and before I could really begin identifying them in the wild, I’d have to spend a lot of time learning both the terminology and the biology of plants. I don’t have the vocabulary or lexicon to accurately describe the shape of the leaf, and I wouldn’t know what other features to look at to ask questions about. But with a smart phone, I don’t need to know anything about plants in order to start learning about them. Machine learning tools like this can be used to jumpstart learning and education in ways that were simply unavailable to us before.

Another great use of machine learning tools for me has been the Google Translate app, which, again, can use a camera on your phone to almost instantly recognize text from another language (say on a restaurant menu, or on a street sign) and convert that text to a wide range of languages. It pastes the text right onto the image in your native language. It’s almost like a pair of glasses that allow you to translate the world around you into your language. It’s genuinely amazing, and I used it multiple times when I was in Kenya this year. While I found it to be a novelty, imagine how powerful a tool like this would be for a foreign speaker trying to fill out insurance paperwork, or medical information at a hospital, or trying to understand complicated legal documents that might affect their rights as a citizen. Tools like this have the power to reshape the way we interact with the world, breaking down barriers as fundamental as language.

Now imagine how the church could use translation tools to quickly translate bulletins, sermon notes, bible study guides, or Facebook and social media posts. Many churches, probably most churches, have people in their community that consider English to be their second language. We could be reaching these people for the Gospel with free tools available online. Of course, these tools are not foolproof, but they could be transformational.

My job has been made substantially easier thanks to applications like Zoom (the video conferencing tool) which uses machine learning to generate captions and transcripts in real time from the audio of the call. This has been tremendously helpful to me as someone who frequently interviews people through platforms like Zoom. Before I used to take notes manually while interviewing people, and now I can occasionally jot down an important point, confident that Zoom will transcribe the verbatim text, and be about 98% correct in doing so.

One of the most tedious parts of my job is writing out the captions for videos that I make, which YouTube’s machine learning tools now automate if you upload the video there. For me, the only job AI is stealing at the CGGC office is the doctor’s visit I’d need for carpal tunnel without it.

A new-ish subscription-based service called “Pulpit AI” allows churches to upload videos of a sermon, and the service will generate sermon notes, devotional notes, bible study questions, social media posts, video clips, and more. It’s a service intended to allow churches (especially small churches) to save time by multiplying the impact of the Sunday sermon. I haven’t personally used this service, but I do see the potential of its utility.

These are all fantastic uses of machine learning that give power to people to do more (and I recognizes that professional translation services probably hate Google Translate, and rightfully so since it’s also probably taken away many jobs in that sector), but regardless, these tools are cool, time saving, opportunity creating technologies.

By the way, did you notice that I almost exclusively used the term “machine learning”, not “AI”? I’m not being pedantic (although I can be quite the pedant). Machine learning has been around for, well, for about as long as computers have been around. The idea that we can let the machine train on data, and then make its own decisions, is not novel. Even small technologies like spell checkers, which have been baked into your computer or phone keyboard for decades, are derived from machine learning algorithms.

Likewise, many of the tools I mentioned predate the explosion of “AI” that started in late 2022-early 2023. The difference is not technology, but scale. And the wave of “AI” tools like ChatGPT that arrived so thunderously in January of 2023 were massive in scale. Massive in their impact, massive in the data sets they trained on, and to that point, massive in how they’ve been breaking the law.

The Bad

Let me say it simply; the creation of modern “AI” is theft and plagiarism on the largest scale possible. And it has happened with extraordinarily little pushback from lawmakers or courts in the intervening two years. While there are substantial court cases being fought right now, the truth is, even if the court cases successfully prove AI companies broke copyright law, it’s far too little, far too late. They scraped and stole the data. They trained the machines and deployed them. They scooped up, boiled down, and synthesized all of the available internet. This isn’t the kind of genie that goes back in its bottle. Not only did these companies not ask if they could, but they intentionally ignored copyright law, and ignored explicit requests by people and companies for their data to be excluded.

Open AI, the company behind ChatGPT, invested in by Microsoft, and at the forefront of the AI craze said the quiet part aloud. In a series of responses submitted to the British House of Lords, OpenAI was asked “What are the options for building models without using copyrighted data?” to which OpenAI said that it was essentially impossible to do, and that it wouldn’t be worth trying. “Because copyright today covers virtually every sort of human expression– including blog posts, photographs, forum posts, scraps of software code, and government documents–it would be impossible to train today’s leading AI models without using copyrighted materials.” We will circle back to whether or not this turned out to be true, or a convenient twisting of the facts.

While I believe this is a pitiful justification, and also a pretty funny way of admitting copyright theft, this statement does clearly outline the problem these companies had on their hands when they started to develop AI models. Without an adequate amount of training data, these models couldn’t make a meaningful improvement over the algorithmic models that have existed for decades at this point.

The issue was twofold. First, startups like Open AI didn’t just need more data, they needed all of the data. Only if they were able to consume all data on the internet would they have the chance of creating something truly revolutionary.

Second, as stated above, the vast majority of that data would be copyright protected, and there was no way they could negotiate legal rights to all of that data. Even the immense amount of investment that OpenAI has seen wouldn’t scratch the surface of licensing costs of all copyrighted data (and can you imagine the paperwork?!) Instead, they decided to steal the data, and fight for permission later. But frankly, it seems like that gambit has paid off handsomely.

ChatGPT sparked an investor lead AI revolution in the tech world. Now, every product showcase, every new tech commercial, and every marketing beat has to have “AI” somewhere in the title, even if the technology isn’t best served with AI enhancements. Investors want to know that the latest technology is being implemented into the latest products. That gives investors peace of mind that their investment is secure and that they’re not investing in a tech dinosaur.

The truth is, the vast majority of these new products won’t have any meaningful AI related entanglement. The only thing AI generated about most of these products is the promotional language surrounding them. While someone can certainly find a way to make your next refrigerator AI enhanced, it is going to cost you $1,000 more, and slow down your Wi-Fi.

OpenAI, and companies like it, are being challenged in court fiercely by large publishers (the New York Times), wealthy individuals (like Scarlett Johanson who believes her likeness was stolen), and other smaller creators. This list of current copyright infringement court cases shows that just about all the big names in AI are being litigated against, because all of them have treated other people’s works as their own.

We’ll see whether or not the court cases align with what we know to be true, but regardless, it’s a demonstration of my most chief issue with all of these tools: they are fundamentally unethical in their creation, and everything they generate will bear that mark.

I don’t see how we, as Christian people, can uncritically embrace tools that are made with such disregard for the dignity of the people who actually made them. Not Open AI, or any other large AI based company like Anthropic, Meta, Google, or DeepSeek, but the artists and authors who created all that training data, who won’t see a dime from it, and whose jobs and livelihoods are currently being threatened by them.

Now, I don’t actually think that most people interested in AI care about plagiarism. I’ve raised this issue with a variety of people, and most just seem to shrug. Stealing other people’s work on the internet is the name of the game, and most people just don’t really value music, art, writing, or creative work right now. Most people expect their entertainment to be free or at best, cheap. But it is a serious issue, and it sits at the very core of how all of these systems were designed. And, because I said we’d circle back to it, a recent study (download here) has shown that it was possible all along to use ethically sourced, copyright free data to create a world class LLM (like ChatGPT), and it was done not by a multi-billion dollar company, but by a relatively small team of underfunded academics. It’s almost like plagiarism was the point.

Unfortunately, there are other serious issues about how these tools work, and what they produce that I think might be more convincing.

A Root Issue

Text generators like ChatGPT have another fundamental issue that will plague them regardless of how well they are trained. They are not truth generating machines, but conversation generating machines. The same is true of image generators and video and audio generators. While a majority of the data they are trained on are probably true facts about the world, their overriding principle, the reason for their existence, is to be convincing, and that bit of foundational programming will win out in a coin toss between reality and unreality.

That is the reason why, if you’re very persistent, you can “hack” chat bots to agree with you. I demonstrated this back in 2023 in a blog post here. If you role play with ChatGPT by saying something like “Pretend you’re a flat earth conspiracy theorist” and then ask whether or not the earth is round, you’re far more likely to get a response that corresponds to the role rather than reality.

Like the algorithms that control our news feeds, current AI systems care more about engagement, appeal, and trustworthiness than truth. That’s why, as Futurism reports, ChatGPT may be latching onto people with a penchant for conspiracy theories or obsessive disorders and exacerbating them. Rather than being fact finding machines that debunk commonly held misunderstandings, AI systems drive people further down rabbit holes and conspiracies in an effort to meet the person’s expectations.

Regardless of whether we have a mental health issue or not, many people will be susceptible to a machine that’s trained to sound human, and that will say anything to convince you it’s trustworthy.

As a people interested in the Truth of the Gospel, we need to recognize that in many ways, what tools like ChatGPT represent is an antithesis to scripture. Jesus does not beg to be trusted but proves Himself. God and His word do not cater to our every fickle desire, but subvert our desires and expectations, showing us a new and better way. So long as our machine learning tools are trained to be convincing, rather than to find truth, we will be engaging with a machine that is actively hostile to discipleship with the One who calls Himself the way, the truth, and the life.

A Deluge of Digital Detritus

The efficiency of AI tools is the feature most touted, and it’s also one of the scariest parts. The amount of text these systems can generate far out strip our capacity to weed through it. Already, humans struggle to grapple with the amount of information available on the internet, and algorithms, designed to maximize your engagement, are keen to keep you scrolling and clicking on whatever interests you.

Search algorithms paired with AI generated content could create bespoke ads, articles, and websites specific to your perceived interests. I already see too many fake videos scroll across my Facebook page. And this will only increase, as AI generated images and video content become easier and cheaper to produce.

In my line of work, we use Lightstock, a stock image website designed for clean, Christian content. Unfortunately, a large portion of the stock images we have access to are AI generated now, and even when we sort for “non-AI Images”, some always sneak through.

Deepfakes are a particularly harmful way that AI is being used. Deepfakes take the likeness of a person, and add it other videos, images, or audio. For instance, one could use an AI audio generator to have Presidents Donald Trump, Joe Biden, and Barack Obama all playing a video game and talking trash to each other. That might be funny. Or as is horrifyingly common, one could use an AI video generator to overlay the face and voice of a celebrity on a porn video.

Recently my wife showed me a compilation of AI generated videos of biblical characters like Jesus, David, and Moses, holding a cellphone and talking into it like they were recording a video. You can watch it here, though you might find it offensive to see Jesus on the cross smiling and talking to his “audience”, or to see a David say he’s going “yeet” a stone at Goliath.

We know that deepfake technology is a genuine worry because the Department of Homeland Security produced a whitepaper which explores the implications and issue with deepfakes. They conclude by saying that “Deepfakes, synthetic media, and disinformation in general pose challenges to our society”, and offer that, “there are those today that claim the Holocaust never existed. Deepfakes could be a nefarious tool to undermine the credibility of history.”

One such fake video is created for good though. Titled “Show this to Uncle Fred before he shares another fake video” the video is a kind of PSA, warning unsuspecting and gullible people to be careful about what they watch and share one, because AI generated video is becoming so convincing, with full audio and quite life like people, that many will be duped. A Warning to Uncle Fred: https://www.instagram.com/reel/DKPu4MppDnj/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

Hallucinations

Even when we try to use AI for good, it has a pesky problem of making stuff up. The word for lies generated by AI accidentally are “hallucinations”. One recent and embarrassing hallucination came from the Trump Administration’s Make America Healthy Again report, which cited studies that didn’t exist, almost certainly because the report was partially generated by AI. The original document was plagued with errors and mistakes in the citations, and the authors attributed made up articles to real people. These issues have mostly been cleaned up in the aftermath, but it’s a perfect example of how even high-level government officials are leaning on AI without a proper understanding of the pitfalls. And this particular administration really should understand those pitfalls considering Elon Musk has been one the leading supporters of AI systems.

AI Isn't Just a Tool

One oft touted rebuttal, which I’ve had tossed my way a few times now, is that “AI is just a tool”. And, so the defense goes, like any tool, AI systems are ethically neutral. What matters is how we, the moral agents, use it.

And there is much truth in the sentiment that we, people with moral agency, need to consider wisely how we use tools. But we deceive ourselves and oversimplify the issue when we pretend tools are neutral in their design, as if some tools are not built bespoke for purposes. Hammers are for hitting nails. Wrenches are for turning bolts, nuts, and screws. Sure, I’ve used a crescent wrench to hit a nail (I was too lazy to go find the hammer), but a hammer is far superior. Likewise, as pointed out by Bryant Francis in an article titled “Is generative AI really ‘just a tool’”, hammers can kill people, but guns are for more efficient.

This line of defense also conveniently forgets that the creators of these tools were themselves moral agents. The people who built these AI systems did so with a purpose in mind, and as we’ve discussed already, their purpose was to make dump trucks of money at other people’s expense. We have already explored how their creation is ethically fraught, and legally questionable. We have demonstrated that AI frameworks are bent towards unreality. And we have experienced how AI systems are being actively used for deceptive purposes.

Scripture tells us that “by their fruits you will know them.” Without being hyperbolic, or talking in extremes, or prophesying the end of civilization by AI overlords, we can say that the fruit of AI just hasn’t been great.

Yes, some people really enjoy using AI. And yes, many companies and individuals are finding ways to use these tools for their purposes. But wouldn’t it be better if we didn’t have to wrangle a tool against its bespoke purpose? Wouldn’t it be better if we didn’t have to use the Super Lie Generator 3000 to author something good, productive, and true?

Unfortunately, while I’m sure most AI systems are being trained to align with truth, there has been insufficient progress in the largest and most popular models, and in fact there has been some regression. Therefore, churches and Christians who embrace AI now ought to do so with an abundance of caution.

AI generated text, images, and video can be rife with errors, and AI shouldn’t be trusted without oversight to produce sermons, bible studies, or translations. Likewise, Christians should wrestle with the ethical questions raised here about how the largest AI models were created, and what they were created for. Perhaps they can be used in a way that redeems them, but that will take very intentional practice.

I think the church offers a paradigm shift away from the unreality of the internet which will become more necessary and more appealing to future generations. The church, both the people and the physical space we worship in, should be clothed in truth and righteousness. Christian people, and the work they do, should be overflowing with genuineness and sincerity.

Lastly, while we can use all kinds of tools to spread the Gospel to every corner of the Earth, we shouldn’t miss the opportunity to be show people how Jesus’s way is different than the worlds. The ripped off, half baked, cynical world that created AI will exhaust people that crave real and authentic relationships. We have the opportunity to show people through our actions that only the real Jesus died for their sins.

CGGC eNews—Vol. 19, No. 24

Login To Leave Comment