We are, I think, so enamored with our own troubles and trials that we cannot grasp the possibility that our struggles are anything other than wholly unique. “Who in the world could possibly understand what I am going through?” we think. And this is precisely why I love reading historical documents. History has a grounding effect. It brings us back to foundations, and it brings us back to sense. Whether it be the Bible or some other firsthand account of history, inevitably we find that those distant people of the past have the same kind of thoughts we have. They experienced the same joys and sorrows, the same successes and the same troubles. Much has been said over the last 2 years of the “unprecedented” nature of this troublesome and quarrelsome pandemic. Much has been said about how our churches must adapt and change in ways that we might be unprepared for. “What will the future look like?”, we wonder, and “how will we navigate these untested waters?” It is, therefore, reassuring to come across a historical perspective that reminds us that, while our situations are neither easy nor insignificant, they are also not wholly unique. We aren’t the first ones to reimagine the church and our approach to ministry. Join me, then, in reading an article written 86 years ago about the state of the Protestant church. (To view the article in PDF form as it originally appeared, click here.)

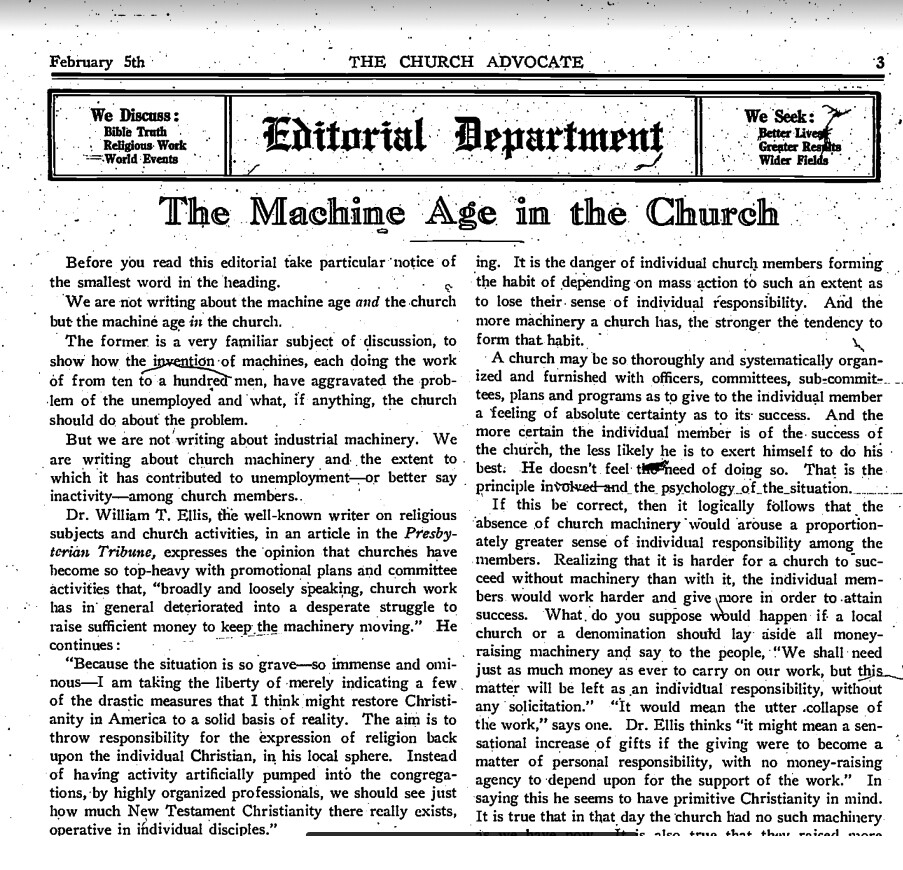

The Church Advocate, February 5th, 1936

The Machine Age in the Church

Before you read this editorial take particular notice of the smallest word in the heading.

We are not writing about the machine age and the church but the machine age in the church.

The former is a very familiar subject of discussion, to show how the invention of machines, each doing the work of from ten to a hundred men, have aggravated the problem of the unemployed and what, if anything, the church should do about the problem.

But we are not writing about industrial machinery. We are writing about church machinery and the extent to which it has contributed to unemployment (or better say inactivity) among church members.

Dr. William T. Ellis, the well-known writer on religious subjects and church activities, in an article in the Presbyterian Tribune, expresses the opinion that churches have become so top-heavy with promotional plans and committee activities that, "broadly and loosely speaking, church work has in general deteriorated into a desperate struggle to raise sufficient money to keep the machinery moving." He continues:

"Because the situation is so grave-so immense and ominous-I am taking the liberty of merely indicating a few of the drastic measures that I think might restore Christianity in America to a solid basis of reality. The aim is to throw responsibility for the expression of religion back upon the individual Christian, in his local sphere. Instead of having activity artificially pumped into the congregations, by highly organized professionals, we should see just how much New Testament Christianity there really exists, operative in individual disciples."

Among other things Dr. Ellis "would release the staffs of most church boards and make the surviving agencies (after many consolidations) merely disbursing offices for the expenditure of funds voluntarily contributed. Mission boards would simply transmit to their fields the money received. All promotional activities would cease. Each Christian's own conscience would be his guide as to where and what he would make his benevolent contributions. It might mean a sensational increase of gifts if the giving were to become a matter of personal responsibility, with no money-raising agency to depend upon for the sustenance of the work."

These quotations will give you an idea-of-the article which contains some suggestions even more radical, with the proposal that all this machinery in the church be dispensed with for a period of five years, as an experiment.

Suppose we assume that Dr. Ellis doesn't expect the churches to take his suggestions seriously enough to adopt them, but that he presents the subject in this way in order to provoke thought, just as a certain minister several months ago, in order to emphasize what he considers the defects in Sunday school work, proposed that the Sunday school be abolished and whatever good work it is doing now be done by the church without a Sunday school.

Even so, Dr. Ellis calls attention to a danger which is very real, and a danger which many churches are not avoiding. It is the danger of individual church members forming the habit of depending on mass action to such an extent as to lose their sense of individual responsibility. And the more machinery a church has, the stronger the tendency to form that habit.

A church may be so thoroughly and systematically organized and furnished with officers, committees, subcommittees, plans and programs as to give to the individual member a feeling of absolute certainty as to its success. And the more certain the individual member is of the success of the church, the less likely he is to exert himself to do his best: He doesn't feel the need of doing so. That is the principle involved and the psychology of the situation.

If this be correct, then it logically follows that the absence of church machinery would arouse a proportionately greater sense of individual responsibility among the members. Realizing that it is harder for a church to succeed without machinery than with it, the individual members would work harder and give more in order to attain success. What do you suppose would happen if a local church or a denomination should lay aside all money raising machinery and say to the people, "We shall need just as much money as ever to carry on our work, but this matter will be left as an individual responsibility, without any solicitation". "It would mean the utter collapse of the work," says one. Dr. Ellis thinks "it might mean a sensational increase of gifts if the giving were to become a matter of personal responsibility, with no money-raising agency to depend upon for the support of the work." In saying this he seems to have primitive Christianity in mind. It is true that in that day the church had no such machinery as we have now. It is also true that they raised more money, in proportion to their numbers and resources, than we are raising now. Even so, this doesn't prove that we should go back to their methods, or rather lack of methods. Progress points the other way. Progress has brought us away from the primitive methods of doing things, both in the world and in the church. The work which the church was established to do is divine, and ever the same. The methods of doing it are largely human, and must be changed to meet the changes of the passing years. There is no more possibility of the churches going back to the days that were without committees, programs and promotional agencies than there is of industry junking all of its machinery and going back to hand labor. But there is no harm in imagining such a thing for the moment in order to get the point of danger with which we started out, the danger of the individual church member depending too much on the multiplied machinery with which the church has become so highly organized and too little on himself. "Plan your' work and work your plan" is a good slogan, but the danger with the individual church member is that of working his plan instead of working himself.

The church is a divine institution. The work it was established to do is a divine work. It can succeed only when inspired and guided by the Holy Spirit. These three facts are the same today as in the beginning, though methods of church work differ. The success of the apostolic church was not due to the absence of plans and programs but to the presence of the Holy Spirit. The Spirit can give success to churches with meager methods, as in the apostolic days, and He can give success to churches with elaborate methods, as in our day. The vital thing is to introduce only such methods into the work of the church as the Holy Spirit can consistently use.

What, then, is the most important lesson of all? It is this: that church machinery is a great blessing when used by the Spirit, but it is a tragic substitute for the Spirit.

End Advocate Article

Eerily familiar, isn’t it?

Jacob Clagg

CGGC eNews—Vol. 16, No. 28

Login To Leave Comment