One of the CGGC’s very first missionaries was Viola G. (Hershey) Cover. Viola was a prolific writer, and regularly contributed to The Church Advocate (now The Global Advocate). She also wrote a book in the early 1900’s titled Glimpses of Bogra, which detailed her experience as a missionary, and included many wonderful black and white pictures of India and modern-day Bangladesh. As one excerpt from the book says, “The churches of God have been aided and stimulated to greater activity by the study and reading of missionary books.” One can imagine that, especially in a time before the internet or even television, pictures of places and people halfway around the globe might be treasures to hold on to and would be a powerful tool for the sake of mission advancement.

Yet, why should we think that the same is not true today? People could, ostensibly, use the internet to search and find millions upon millions of pictures of life in Bangladesh and India. There is essentially no end to the number of pictures, text, audio and film, readily and freely at a person’s disposal. We need only pick up our phones, and we have a portal to see anything we might dare to see on the other side of the world, much of it curated to move you to compassion. The problem isn’t a lack of material, it is that we will not look.

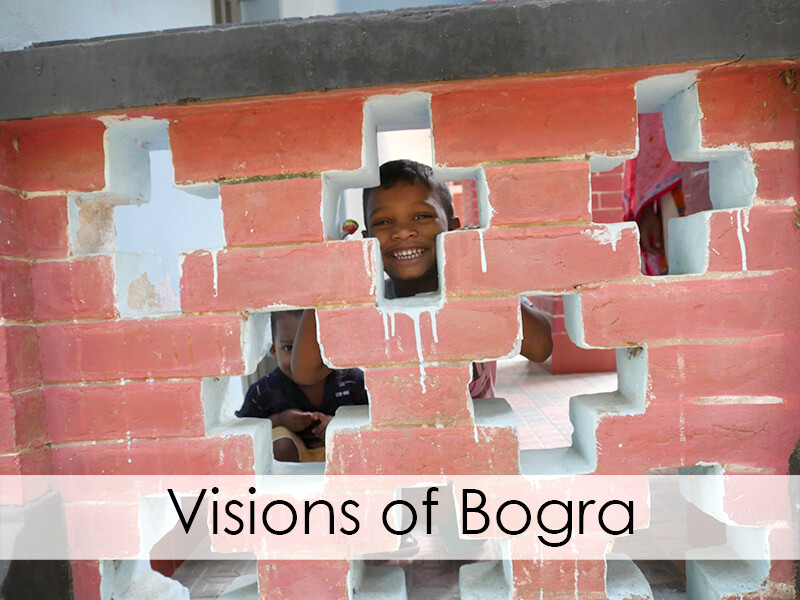

Many of us think we already know enough, and so we don’t need to look. But I will tell you with the utmost conviction of my soul, you need to look. I work in the office of the CGGC. I have for a full year, and there is so much I did not know precisely because I thought I already knew. This is a failure of both imagination and communication, and it ought to be rectified. If I did not know from this office, how can I hope anyone outside will know either? This article will be then a new attempt to help people see and know Bangladesh and our mission work there. It will be one of many over the coming weeks, months and years. More articles, more pictures, videos, and sound clips. And on special occasions we hope to bring our Bangladesh Field leaders to your local church, so they can speak directly to you. In the same way that Miss Viola hoped to give her readers a glimpse of Bogra (now Bogura) in the early 1900s, we hope to give you a vision for what Bogura (and all of India and Bangladesh) is and could be 100 years later.

Bogura

When Viola (Hershey) Cover went through Bogura for the first time in 1905, Bogura had “one main street,” a railroad that “passed through the center of the town” and a population of about 5,000 people, according to Viola. Now, Bogura city (for it would be improper to call it a ‘town’ now) has hundreds of streets, multiple railways and a population of close to a million people. A lot can happen in 120 years.

In many ways, Bogura resembles a modern city. Streetlights, sidewalks, multi-story buildings, cables running every which way, all supporting a ceaseless wave of traffic, both vehicular and pedestrian. Among this mixture of concrete, brick, and stone, are the occasional patches of green in the city, and one of the largest patches belongs to our Bogura Mission. Indeed, if you arrive at night, like I did, you’ll step out of a van and find yourself looking up at a canopy of trees, not city lights. It’s the sound scape, a noisy cacophony of car horns, that gives it away. When you reach the edge of the campus, that’s when you realize (or at least, when I did) that our mission in the forest was actually surrounded by 6 and 7 story apartment complexes.

Bogura Mission Sign, House in the Background

Bogura Mission Sign, House in the Background

Within the walls of the campus is the Mission House itself, along with a schoolhouse, a church, multiple buildings for the hospital and nurses, housing for staff, and a hostel. On the days I was there, the central courtyard was a quiet place with women cooking and washing clothes, children playing in the school yard, and stray dogs eyeing me to see if I’d give them affection or something to eat.

Three neighborhood children laying on the church steps

Three neighborhood children laying on the church steps

Our team met with the teachers of the school who, as is custom, welcomed us with flowers. But we were really there to see the state of the school, and to ask the teachers what they needed. Dressed in their traditional saree clothing, the teachers (and one adorable daughter) talked to us about their hopes of doubling their enrollment for next year through door-to-door campaigning. It’s an ambitious strategy, but they are confident. While it’s mostly a memory for us, fears of Covid are still high in places like Bogura, and parents are hesitant to send their little ones to a crowded school. Having seen the empty school rooms, the off-kilter doors, rusting hinges, leaking roofs, and dust covered… everything, we had obvious questions about the staff’s capacity to accommodate twice as many students.

L to R: Literature Teacher, Oppi Das, Travis Helm, School Headmistress, Bob Fall, David Odegard

L to R: Literature Teacher, Oppi Das, Travis Helm, School Headmistress, Bob Fall, David Odegard

That’s when the needs poured out. They need more of everything. More chairs, desks, bookshelves, and furniture. Likewise, more pencils, papers, worksheets, supplies, and computers. They recognize that they will even need more staff, and more training for their staff would be good too. As a case in point, the “computer lab” was a room with two ancient computers, both of which are now non-functional. The humidity of Bangladesh plays nightmares on technology. The teachers “teach” computer classes by demonstrating how students could use one (what the keyboard does, how the mouse works), in an entirely hypothetical manner. They sit in front of a dead computer and learn theory, not praxis. It was at this point that I actually understood the depths of the need, and the courage it takes to teach at a school with so little.

The teachers, smart, funny, young, and talented, stretch themselves thin teaching students with the bare necessities. Accomplished people, who could probably do better for themselves in another occupation, work on our Mission campus, rationing materials, and dreaming of a time they can give their students a taste of real technology that the world operates on. They do this because they believe in the Mission, and because they don’t want their students to fall behind. There and then I had a vision of what the school could be.

By mid-morning, the hospital grounds were already crowded with people waiting for an appointment. Inside the facility it was even more densely packed. The maze-like, multi-storied building was full of waiting rooms, hallways, stations, and procedural rooms. It felt to me that every square inch of standing space was occupied. My camera footage, held at my abdomen, and mostly pictures of other peoples abdomens, reflects the claustrophobia I felt setting in. Again, the humidity wasn’t helping.

Nurses in white uniforms, and learners in their sarees moved about, taking time they probably didn’t have to greet us and welcome us. Meanwhile, patients sat, stood, or laid down, in every spot they could find. The men looked impatient, while Muslim women, covered head to toe in a Niqab, gave indecipherable looks with the only visible part of their face, their eyes. The nursery and pediatric wards were overflowing on the day we were there. Mothers and their infant children sat on hospital beds (more like cots) in rows and rows, and spilled over into rooms typically for other patients, but this day they needed the extra space. Some were kind enough to look at us while we only increased their lack of privacy. Others covered their faces with veils when I took a picture. I stopped taking pictures after that.

In nearly every operating room, we found equipment purchased directly by the CGGC through generous gifts of many donors. Sometimes large machines, sometimes small, but always accompanied by grateful doctors. Like the school, seeing the tangible ways we can partner with the hospital immediately casts a vision for what Bogura Mission could be. The hospital is already, obviously, doing tremendous work. Serving hundreds of thousands of people a year. How can we partner together to do more? I walked into the newborn nursery, and three babies born that day were laying on a table in separate basinets. One had an acrylic breathing box over its face. Medical tape was holding the box together. A baby’s life, held together with tape. I thanked God for the tape, and saw a vision of what Bogura should be.

Outside of the hospital, we walked into a wooded area behind the school where some of the workers live. While in other places on the campus, I could pretend for a moment that I wasn’t in the city, here, the mosquitoes and overgrown vegetation convinced me thoroughly that I was in a Bengali forest. A little ways down a dirt trail and we came to two small houses. Painted white once, but time and mold have chipped away, and gray black bricks climb up the front, all the way to the rusted sheet metal roofs. Out front vibrant clothes are hung to dry and a child’s play trike rests. The residents, 7 or so people, came out to meet us, and watched as we had our little tour of their homes. We smiled and waved, but my eyes were drawn to a narrow gutter, dug into the dirt, running between the homes and into a small bog about 200 feet away. Chickens were standing in the gutter, and gray water slowly flowed by.

“Yeah. It’s what you think it is,” one of our guides told me. Sink water, clothes washing water, and everything else.

I walked toward the bog despite a warning, and snapped a couple of pictures. When I came back out the residents were happy to have me take their picture and were kind enough to ask for a picture of me too. When I left, I stepped over the gutter where chickens pecked, mosquitoes bred, and people lived. I looked at the dark bog, itched a fresh mosquito bite, and had another vision for what Bogura could be.

The Bengali Dichotomy

The most shocking thing about Bogura specifically, but true of the rest of Bangladesh that I saw, is how harshly the beautiful and the terrible clash in every village, street, shop, rice field, and home. The people and the natural environment of Bangladesh are vibrant and beautiful. You have probably never seen so many shades of green, or marveled at how one word could mean so many different things. Likewise, our earth tone saturated world, full of browns, creams, and (the Lord forbid) every shade of beige imaginable, is practically assaulted by the vibrancy of the traditional saree dress so many of the women wear. The sights and the sounds in Bangladesh can be so much that I found myself lamenting my fascination with drab, and my wardrobe of gray, dark gray, and black.

Especially in the countryside, in the dark, on dirt roads, driving is a nightmare. Busy, dangerous, and unimaginably chaotic. Every vehicle imaginable. Buses, tractors, vans, trucks, cars, trikes, bikes, motorcycles, and bipeds. People walking in the middle of the road. Toss a few goats and a pack of dogs onto the road too and you start to get the picture. Everyone passes everyone else. People push and honk with abandon, and yet somehow, no one seems to care that much. Passengers stare at their phones, and the drivers honk their horns ad nauseum almost as a matter of principle.

There is no end or beginning to the road. The road runs onto the curb, the curb to the sidewalk, the sidewalk into the shops. Meanwhile, people move about, like a wave of human and animal bodies.

The villages and the cities are texturally chaotic, almost incoherent. Sheet metal, timber, concrete, red bricks, piles of red bricks, both stacked and in a heap. Dirt piles, dirt holes, plastic tarps, thatch roof houses with neon lights on top. Everything seems to have been built without regard for architectural consistency. It’s all practical demand, transforming old world villages into Vegas, one neon sign at a time. Marble facades have bamboo stick fences. Every square inch of a building is covered in a bright red advertisement. Modern political propaganda hangs from trees, not telephone poles. Meanwhile, modern telephone poles are piled up on the side of the road. Construction starts soon, or maybe the construction is over. I can’t tell. Construction never seems to fully begin or end in Bangladesh.

Everything is being fully utilized, while simultaneously being built. The Bengali people use all of their available means to construct their world and to live their life. But that means that every building is both being used and being built. Every street is under construction and full to capacity. Every hotel has an entire floor being reworked. Every bathroom has a broken toilet seat (if it has one at all).

Men and live stock spill over the top of a truck on a Bengali highway.

Men and live stock spill over the top of a truck on a Bengali highway.

Meanwhile, the conditions of the countryside and the city dilapidate and ensure that everything older than a few days (even the vegetation!) has a coat of dust, dirt, or mold forming on it. It’s incredible. Uncanny. Terribly human.

The impression is then of a place of many wonderful, kind, beautiful people, densely populated, striving for life amidst structural and cultural systems that wage war against practical necessity. It is a world of tough people pushing through immense problems. And it is in the midst of that pushing and striving that our Mission in Bogura exists and thrives.

In a country of 90% Muslim, 5% Hindu, and less than 1% Christian, our 125-year-old Mission is building community, treating the sick, teaching the young, and bringing people to Christ all along the way. So attractive is the work our Bengali brothers and sister do that many Muslim people work with us and for us. They might not confess Jesus yet, but they can’t deny the good He brings. And when you go to Bogura you cannot help but have a vision for how we can partner together to do more.

What we can do.

It's cliché to go to a third world country and upon returning have my whole personality changed by it. It’s cliché because I’ve seen it happen before to plenty of people. There’s a slight (maybe not-so-slight) cynicism in me that reflects on how mission trips and excursions to third world countries often show up on Facebook, and Instagram as an album, but rarely in the form of a genuinely changed person. It’s especially cliché because of just how quickly we return to our normal lives and allow the impact of the experience to fade.

It's not that short term mission trips don’t have powerful emotional and religious significance for people. Of course, they do! But at some point, quickly or slowly, we forget what made us care. We might scroll back through pictures on our phone or glance at a souvenir we brought back with us, for it to rouse only a small fraction of the emotional response we felt then, thousands of miles away from home.

It stops mattering to me in the way it did then. The faces of hungry children get covered over with a patina. Their plight somehow seems more tolerable. I recall how I felt then, but I can’t make myself feel it again now.

I’m worried that now that I’m home I’ll forget Nancy, Norallom, and Oppi. I’m worried I’ll forget the ways my eyes delighted in the colors and beauty of Bangladesh and India, the ways that my heart ached when I saw the sweet children, and the faces of new friends when I had to leave each location, or the way my anger burned at the sight of so much trash, litter, and pollution, or the way my stomach churned at the sight of hardworking people living next to a gutter filled with grey water, fecal matter, and flies that consumed it.

There are so many problems to fix, but unlike here in the U.S., all of them feel preeminently fixable, precisely because we have such excellent leaders in Bangladesh who have demonstrated their capacity. Our power to make change here extends so much further than it does back home. Through faithful service, good stewardship, and the grace of God, we can manage our way out of these problems. We can fix the broken and molded houses. We can provide school materials, computers, and supplies. We can address the needs of our hospital in Bogura, and our Eye Clinic in Joypurhat. And we can do all of it for a fraction of the cost, and a massive return on investment.

Our Bangladesh mission recently celebrated their 125th year doing ministry, and we couldn’t be prouder of the work being carried out by our Bengali brothers and sisters. But they should not be left alone to bring souls to Jesus, heal the sick, teach the young, provide jobs, and feed the hungry without our help. We have tremendous resources available. While we struggle against our culture of religious apathy, our Bengali brothers and sister are taking the message of Christ to new villages that have never heard of Christ before, and they are excited to learn about Him.

Giving Tuesday is right around the corner, a time when you can directly support the field leaders like Dr. John Costa in Bangladesh. Likewise, over the next year, we will have targeted projects in Bangladesh to address specific needs in our schools and hospital there, and these projects will need funding. We will come asking, loudly and proudly for you to partner with our Bengali brothers and sisters. Will you partner with us to see the message of Christ reach those who need it? Will you entrust what God has given to you into the hands of faithful believers who have a proven record of incredible ministry?

CGGC eNews—Vol. 27, No. 44

Login To Leave Comment